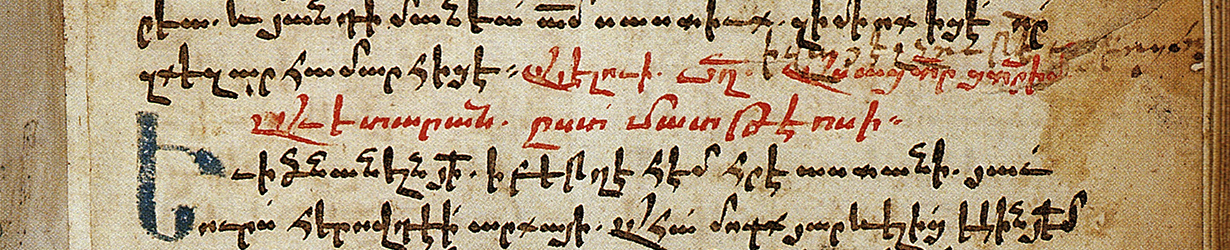

The Armenians, who have shared in the creation of the country’s cultural landscape since the fourteenth century, constitute one of the most significant incoming (allochthonous) cultural collectivities in Poland. First, from the fourteenth century to the eighteenth century, they called forth a cultural turn known as Orientalisation by pioneering the eastern trade through the mass importation and production of goods from the Orient (understood broadly to include Persia, Asian parts of Ottoman Empire, India and China, but also Egypt) and by catering for the needs of the upper levels of Polish society. There is much to suggest that these Kipchak-speaking Armenians prepared the ground for the adoption of Orientalisms in Polish through their commercial practices. The career of the word kurdesz in popular culture – from Turkish kardeş – brother, arkadaş – companion – is an expressive example (see Franciszek Bohomolec’s poem Kuredesz nad kurdeszami, which refers to the lives of an Armenian family in Warsaw). During the same period – as experts in the politics and languages of Persia and Turkey – they supplied the Polish state with useful, practical knowledge of Oriental empires. In the south-eastern borderlands of Poland they took part in the formation of the urban spaces (such as Lwów, Kamieniec Podolski, Jazłowiec, Stanisławów and Zamość), and from the nineteenth century in the shaping of the agriculture (large-scale agricultural properties in Eastern Galicia and Bukovina). In these lands of pronounced ethnic diversity their loyalty to the new fatherland fortified the social potential of Polishness. Already from the eighteenth century they were, as writers, preachers, doctors, lawyers and as professors of the academies at Zamość and Kraków, important participants in the transformations of the mainstream of the intellectual, literary and religious life of Baroque and Enlightenment Poland. As bankers and manufacturers they were to the fore in new fields of economic life too. Simultaneously they nurtured their inheritance, which combined the ancient Christian culture of Armenia, which reached back into the fourth century, with the distinct linguistic identity (the Kipchak ethnolect; later Polish), religious identity (Catholicism) and outlook (Occidentalism) of the diaspora they created in Poland. The result was their own version of Armenianness, which is denoted in Armenian by the word Lehahayer (Լեհահայեր) – meaning Polish Armenians. Its cultural legacy is still with us in the form of literature and documents in four languages: Armenian, Kipchak, Polish and Latin. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries they made up influential elements of two layers of Polish society: the landowners and intelligentsia, and they became active in Polish political life in the movement for national liberation, in the agreement between Poles and Austria (the so-called Polish autonomy) in Galicia and in the construction of the reborn Polish state and nation. As one of the minorities that bound its lasting fate to the Polish national interest, it produced a galaxy of outstanding Polish political leaders. In 1918-1939 during the Second Republic there occurred an ethnic renaissance of the Polish Armenians: new organisations were established, the press was born, academic research was undertaken and plans were laid for a museum.

Coat of arms of the Polish Armenians

(designed by Katarzyna Agopsowicz, 2017)

Poland’s loss of the eastern lands following WWII signalled an existential crisis for the Armenian collectivity. It was deprived of all of its institutions and structures, its entire native land, every one of its temples, as well as very nearly all of the material heritage accumulated over its five-hundred-year existence. This happened suddenly in the space of a single year (1945-1946). The cruel murder of a proportion of the collectivity in the course of war, occupation and genocide had happened in the preceding five years (1939-1945). After the war, the survivors were dispersed about the globe. This exodus heralded the loss of collective identity and memory. Over the following decades in the former centres of the diaspora of the Polish Armenians (now on the territory of western Ukraine) architectural monuments fell into ruin, archives deteriorated (and until recently remained difficult for researchers to access) and the collections destined for a planned Armenian Museum were dissipated. To write the history of the Polish Armenians is therefore one of the priorities for research into Poland’s past. This is true both in substantive terms (the Armenians played an important role in Poland’s history) and in social terms (the risk of obliteration of cultural traces and loss of memory of them).

The Encyclopaedia of the Polish Armenians is envisaged as a project of the Foundation for the Culture and Heritage of Polish Armenians in Warsaw that is written and edited by members of the team at the Research Centre for Armenian Culture in Poland (RCACP) assisted by invited co-authors and reviewers of individual headwords.

Encyclopaedias covering entire cultures are a fairly common way of ordering and disseminating knowledge about them. They were first taken up by students of Jewish culture (The Jewish Encyclopedia, 1901-1916) by students of Polish culture (Zygmunt Gloger’s Encyklopedia staropolska, 1900-1901 [Encyclopaedia of Old Poland]); Encyclopédie polonaise, 1916-1918; Petite encyclopédie polonaise, 1916) and by students of the Muslim peoples (Encyclopédie de l’Islam, 1913-1938). The encyclopaedic approach, which harnessed formidable investigative strength to focus and integrate the various specialist disciplines, created a store of knowledge of unusual intellectual fecundity. Alongside further Jewish encyclopaedias, the most famous of which was Encyclopaedia Judaica, there also appeared Encyclopædia Iranica, the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, and the Encyclopedia of Rusyn History and Culture.

As these volumes do, and taking a multidisciplinary approach, the Encyclopaedia of the Polish Armenians will offer a detailed, faithful, but also broad, history of a society that has been active within the shifting borders of Polish territory for almost seven centuries, that, between the fifteenth century and the eighteenth century was probably the most important of the world’s Armenian diasporas, and that has played a remarkable role in the culture of Central and Eastern Europe. This role has been largely forgotten and is neglected in international historical literature. As a result of the spread of the stereotype of its rapid and complete assimilation as a result of church union, one might argue that the memory of the Armenian diaspora in Poland has even been distorted in the historiography of Armenia. Meanwhile, in the national historiographies of the new countries that emerged in the eastern parts of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Ukraine, Belarus), there is a tendency to remove this collectivity from the context of the real historical process.

However Poland can now boast a considerable number of detailed, monographic and general studies of the Polish Armenians, and can confidently assert that the progress of research in this field has been particularly dynamic in recent decades. Our understanding of the extant sources, which have been scanned and collected in a single database stored at the Foundation for the Culture and Heritage of Polish Armenians in Warsaw, has also increased. Progress has furthermore been made in producing critical editions of them, which include the sources in the Monuments of the History of the Polish Armenians series. The stage is therefore set for an encyclopaedic treatment, which will appear in both English and Polish versions and so be available to a global audience, including those most interested in Armenian humanities, of whom few know Polish.

As with the other encylopaedias mentioned above, the aim is to systematise knowledge of the culture of the Polish Armenians, to fill the gaps that still exist in this knowledge, to attempt to resolve – or at least describe – research controversies (such as the direction of, and reasons for, acculturative identity changes), to consolidate and mobilise the domestic and international research community, and to disseminate a view of this culture in a correctly reconstructed historical context that is free of political distortion and as objective as possible.

Its structure is modelled chiefly on Encylopaedia Iranica. It will therefore feature succinct, general headwords rich in information, but will not be an encyclopaedia of the classical sort that attempts to include the maximum number of headwords and so provides less information in a sparse style. After all, certain questions cannot be answered without examining multiple perspectives, including the different research positions that exist in relation to them.

Based on the literature, it is estimated that it will contain approximately five-hundred headwords of a length ranging from three-thousand characters to thirty-thousand characters and include treatments of iconography and cartography, as well as a bibliography.

Six themes are covered by the headwords:

• the geography of the Armenian diaspora on the Polish territories within their shifting historical borders and of the network of Armenian Polish collectivities beyond them (Bukovina, Bessarabia, the Caucasus, Transylvania and – mainly since WWII – Great Britain, Australia, Canada and the USA) whose origin lay in secondary migration with retention of the specific identity formed in Poland (brief monographs on the Armenian collectivities in the various towns and regions)

• biographical literature

• linguistic and literary phenomena (languages, literature, the press) cultural achievements (art, architectural monuments)

• economic phenomena (organisation of trade and the crafts, agriculture, banking) political phenomena (participation in diplomacy, parliamentarianism)

• socio-cultural phenomena (migrations, the family, structure of the communities, history of the church, legal questions, ethnic organisations, symbols, folklore, customs, collective memory, ethnic bonds, holy days, acculturative phenomena, relations with other societies, commemorations)

• historiography of the Polish Armenians (achievements, sources, legacy, heritage)

Compiling the Encyclopaedia of the Polish Armenians, and thereby structuring knowledge and addressing gaps in research concerning a cultural group that has played an important role in the cultural history and identity transformations of Central and Eastern Europe, makes it possible to undertake comparative analyses and theorisations in areas such as linguistic and religious relationships in the borderlands, the role of economics, law and art in acculturation and integration, the relationships between majority and minority societies and between the various minorities, state mechanisms for managing cultural diversity, the role of incoming or allochthonous groups in economics, in mediation between civilizations and in mediation at the regional level, and the significance of inter-ethnic conflict and rivalry in social life. An encyclopaedic treatment makes historical knowledge easier to use for scholars of other disciplines, such as sociology, anthropology and political science, who are interested in the research topics set out here.

We invite contributions from researchers from a variety of countries, especially those whose histories cannot be fully understood without taking account of the Polish-Armenian context: Armenia, Ukraine, Belarus, Romania and Hungary. When combined with publication in English, this makes it possible to internationalise research findings and impart energy and impetus to investigations on a broader scale than if they were conducted by Polish scholars alone. It should also be noted here that the literature, which contains myths and stereotypes about the Polish Armenians, reflects ignorance of both their role and cultural importance. Publication will, at the least, facilitate discussion of these myths and stereotypes, and it may also excise many of them from the field of research. Such a cleansing will surely be beneficial, and lend further studies a more rational tone.