Instructuarius per me descriptus Stanislaum Piniecki Anno Domini 1691 Die 26ta februarij Oblatus M[agno] Domino D[omi]no Danieli Zarugowicz Thelon[eatori] S[acrae] R[egiae].M[aiestatits] et R[ei] Pub[li]cae Superintendenti Anno Domini 1692.

Instructuarius per me descriptus Stanislaum Piniecki Anno Domini 1691 Die 26ta februarij Oblatus M[agno] Domino D[omi]no Danieli Zarugowicz Thelon[eatori] S[acrae] R[egiae].M[aiestatits] et R[ei] Pub[li]cae Superintendenti Anno Domini 1692.

This is the full title of the manuscript recently purchased for the collection of the Research Centre for Armenian Culture in Poland. It is a unique relic of the history of international trade and customs policy in the Kingdom of Poland at the turn of the eighteenth century. It was drawn up in 1691 for Daniel Zarugowicz, a Polish Armenian, who served as a superintendent of the Russian and Podolian customs authorities.

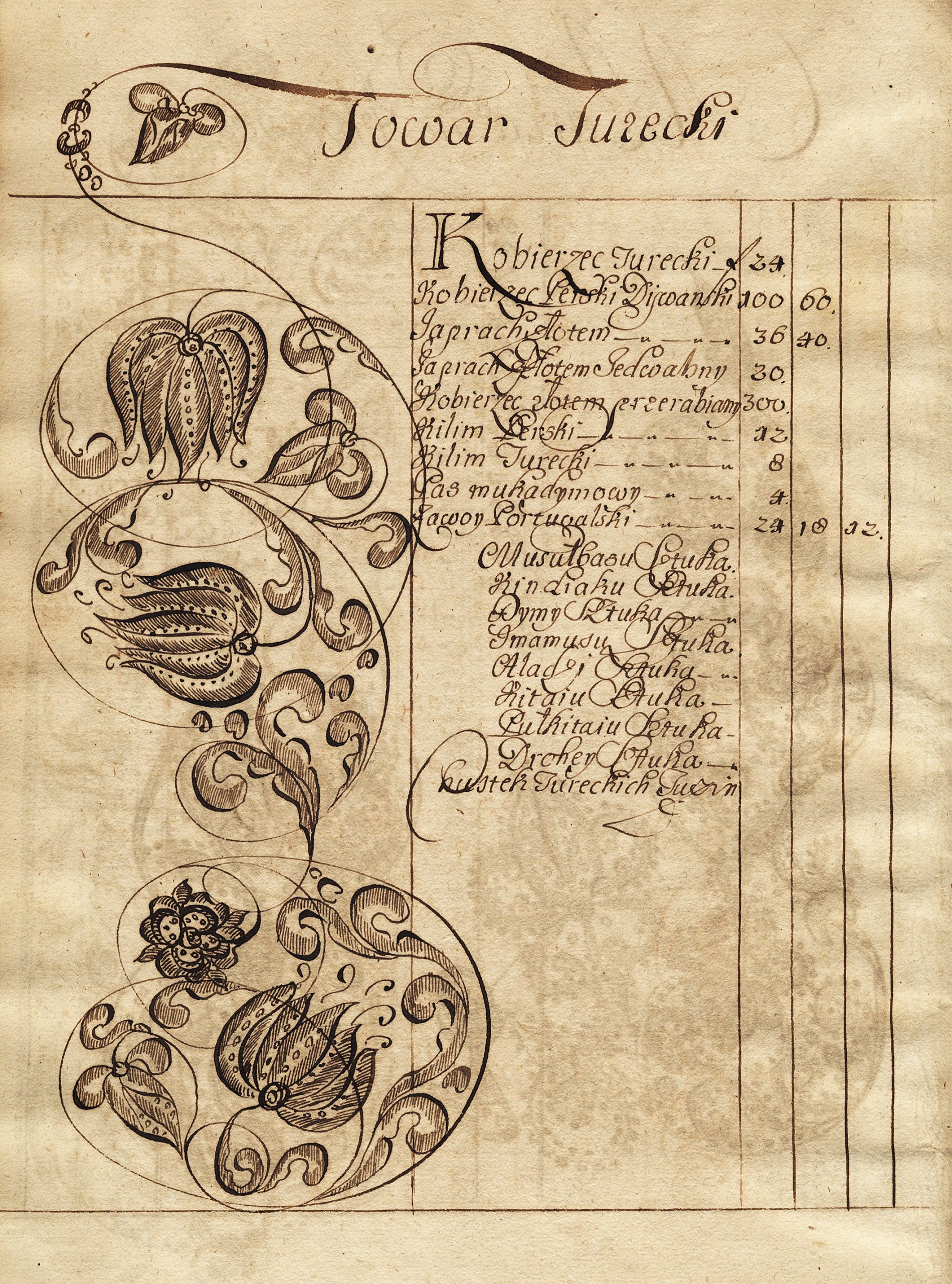

The manuscript, beautifully decorated and calligraphed, contains instructions for collecting excise duties, lists the names of all goods transported across the Polish borders, the amount of excise duties for a specific measure of each, and the place of collection (customs chambers). It is also an excellent source for the history of the trade and production dimension of the Polish language in the Old Polish Era. It contains many names of textiles, agricultural goods and metal products, for example.

The manuscript is also of great importance in the history of the Polish Armenians. It concerns the activity of a person of great importance in this community at that time, involved in church, social, colonisation and mercantile affairs. Zarugowicz was especially active in Kamieniec Podolski, Lviv and Zolochiv. He is also famous in the history of Poland because of his long period in office at a turning point (a crisis of Ukrainian customs duties after the construction of St. Petersburg with its seaport and the change of trade routes that hitherto had come from the east through Poland). In 1715, Zarugowicz was accused of abuse and murdered without a court sentence by treasurer Przebendowski, the head of the customs service, to cover his own embezzlement. While a dozen or so years earlier, civic opinion in Poland was almost unanimous in thinking similar accusations were true (against the great tycoon of money trading in the Kingdom of Poland, Jakub ben Natan Becalal of Zhovkva), no one believed in Zarugowicz’s guilt. His tragic fate was strongly echoed in the politics of the time; it triggered a protest by the voivode of Podolia, Stefan Humiecki, and was debated in the Sejmiks and Sejms and during the Tarnogród confederation.

Zarugowicz’s manual will be published in a critical study by the Centre’s employees next year.